BEIJING - China's ruling Chinese Communist Party (CCP) will be holding its five-yearly national congress from Oct 18 at which a leadership transition will take place.

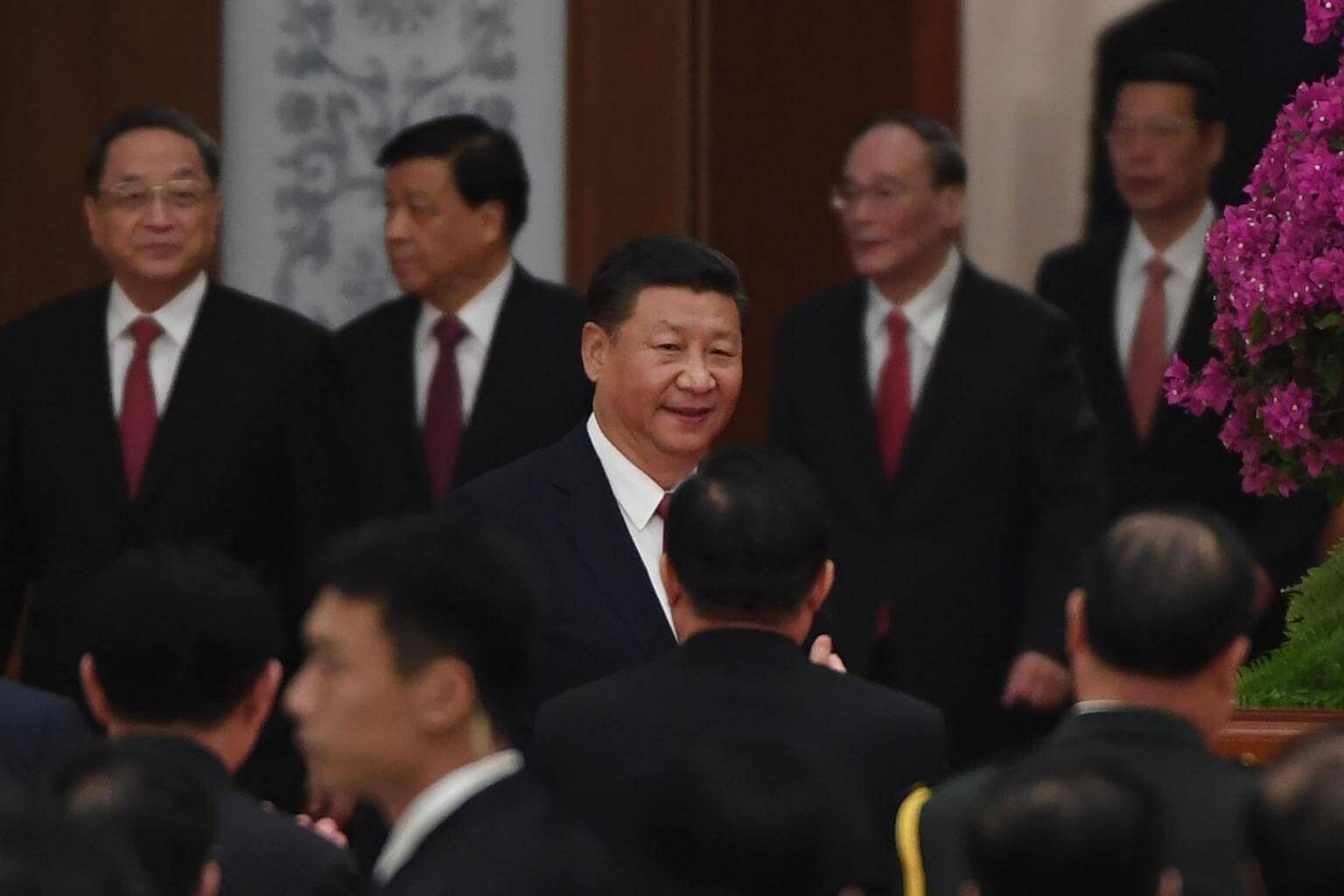

This transition is expected to strengthen further President Xi Jinping's already strong grip on power over party and state. Mr Xi, also the party's general secretary, is expected to be able to promote mostly his allies to top party positions and to have his political thoughts written into the party Constitution.

This consolidation of power will allow him a relatively free hand over party and state policy over the next five years.

As the events unfold, the 19th party congress will be able to offer some answers to these seven key questions about China.

Will it mark the dawn of the Xi Jinping era?

Many China watchers have remarked how President Xi Jinping has amassed power quickly since taking over the reins of the CCP in 2012, and to such an extent that some consider him to be the most powerful Chinese leader since Deng Xiaoping.

But it has been by no means an easy task.

When Mr Xi became general secretary, the new members of his teams, the seven-member Politburo Standing Committee (PSC) and the 25-member Politburo, were not mostly his allies. Instead, they were picked by his predecessors Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao.

To get round the power-sharing within the collective leadership and resistance to his policies from some colleagues who are not necessarily aligned with him politically, he set up new small leading groups headed by him or put himself in charge of existing ones. These groups are high-level steering committees that guide policies.

For example, economic policies are normally driven by the premier, but Mr Xi put himself in charge of the leading group for financial and economic affairs, usually headed by the premier. He made Premier Li Keqiang his deputy in the group, weakening Mr Li's power.

In addition, he started a wide-ranging anti-graft campaign which was meant to rid the party of endemic corruption but also got rid of his rivals and members of vested interest groups who were resistant to his policies.

He implemented military reforms that not only modernised the People's Liberation Army, but also put him in direct command of the military.

In October last year, he was made the "core" of the party leadership, increasing his status a notch.

This year, there was a drive to write his political thoughts into the party Constitution and it looks likely to happen at the 19th party congress.

This will consolidate his power further, and boost his ability to promote his proteges into key positions in the party leadership at the same congress.

A third move, which some analysts like Professor Zheng Yongnian of the East Asian Institute of the National University of Singapore have suggested, is the changing of the post of general secretary to that of chairman.

The general secretary is just first among equals - he is like a "class monitor", said Prof Zheng at a recent talk in Singapore - but a chairman with one or two vice-chairmen reporting to him will have greater authority. Analysts believe this might happen at the upcoming congress or the one in 2022.

If Mr Xi has his way, he will have amassed even more power by the end of the congress and will have it easier when pushing his policies and reforms over the next five years of his rule. Or as an editorial in the Hong Kong newspaper Ming Pao said, "the Xi Jinping era has arrrived".

And, as some suggest, he may even go for a third term in office, breaking with what has been widely seen as an unwritten norm of two five-year terms for the party's top leader.

Will he be able to stack more allies to key positions?

That various members of the two top decision-making bodies are expected to step down at this congress gives Mr Xi an opportunity to promote his allies to these key positions.

The CCP holds five-yearly national congresses at which a new central committee is elected by the more than 2,000 delegates representing its more than 88 million members.

The central committee in turn endorses members of the Politburo and the party's top decision-making body the PSC.

However, observers say such elections are mere formalities. Before the party congress takes place, the new members would already have been decided through horse-trading among various factions of the party, at various meetings, including at the yearly summer retreat at the beach resort Beidaihe in August.

Some observers like Hong Kong-based Willy Lam have said that things could still change even right up to the last weeks before the congress.

There are some unwritten rules regarding the selection of new members to the two bodies.

One is that members of the new PSC are drawn from the current Politburo with the exception of younger leaders promoted in preparation to succeed as party general secretary and state premier, wrote China watcher Dr Alice Miller of the Hoover Institution.

There is also an unwritten retirement age of 68 determined at the 16th congress in 2002 that has been followed since, analysts have said.

This means that whoever is 68 or above at the time of the congress will have to step down. Those 67 and below can hope to be promoted to higher office or stay on in the Politburo for another five years.

According to this age-limit rule, around four or five members of the current seven-member PSC and around 10 or 11 of the 25-member Politburo will have to step down at the upcoming congress.

Given that PSC members are chosen from current Politburo and that many of them are allies of Mr Xi's predecessor Hu Jintao, Mr Xi will find it hard to fill all the vacant positions of the PSC with his men unless he reduces the number of the PSC from seven to five.

As for the Politburo positions up for grabs, Mr Xi, in the past five years, has been fast-tracking his own proteges and people who have shown loyalty to him to positions of power that will allow them to be promoted to the Politburo.

These include those who have worked with Mr Xi when he was in leadership roles in Fujian and Zhejiang provinces, and financial hub Shanghai, such as new Chongqing party boss Chen Min'er and Beijing party chief Cai Qi.

How many of his own allies Mr Xi will be able to appoint to the Politburo will be one of the measures of the amount of power he has accumulated.

Who are likely to be elected to the PSC?

Arguably, the most keenly watched event will be the unveiling of the members of its top decision-making body, the PSC.

This will take place on the last day of the gathering after the first plenary session of the new Central Committee.

There has been speculation that Mr Xi might reduce the number from the current seven to five in order to ensure a majority of his allies in the line-up as well as to avoid naming successors-in-training to the team as has been the unwritten norm.

The PSC currently has seven members, including Mr Xi and Mr Li. The PSC is selected from the 25 members of the Politburo.

Observers believe that Mr Xi would like to keep Mr Wang Qishan, his anti-corruption czar and a trusted ally, on the PSC, possibly in an economic post given his vast experience in this area.

Mr Wang, at 69, is above the age limit for staying on. However, in October last year, a senior official with a party think-tank said any convention regarding age limit was party practice that "can sometimes be adjusted as needed", a remark that appeared to pave the way for Mr Wang to stay on.

At the same time, media reports, including some from Hong Kong, have said Mr Wang wants to step down.

Other members of the current Politburo, from whom PSC members are normally drawn, who are linked to Mr Xi include Mr Li Zhanshu, 67, director of the party's Central General Office, whose friendship with Mr Xi goes back three decades to when both were local officials in Hebei province.

Another confidant of Mr Xi is Mr Zhao Leji, 60, head of the Organisation Department that takes care of personnel matters. Both Mr Li and Mr Zhao are likely to be promoted to the PSC.

Another strong contender for the PSC is Vice-Premier Wang Yang, 62, who together with Premier Li Keqiang, belong not to Mr Xi's camp, but to the Communist Youth League faction - or tuanpai - of which power Mr Xi has sought to weaken.

Others more neutral but leaning towards Mr Xi are Shanghai party secretary Han Zheng, 63, who had worked with Mr Xi when the latter was briefly the Shanghai party secretary in 2007 and Mr Han the mayor; and Mr Wang Huning, 61, Mr Xi's key policy adviser.

The sole sixth-generation Politburo member with an outside chance of entering the PSC is Guangdong party boss Hu Chunhua, 54, who belongs to the tuanpai. Another is Mr Xi's protege, Chongqing party chief Chen Min'er, 57, who is not a Politburo member.

How will the world's largest military evolve?

Mr Xi is likely to speak on military reforms that have been carried out since he took office in 2012.

The People's Liberation Army (PLA) has undertaken reforms since 2012 that have turned it into a leaner and more effective fighting force, and also one which is more closely aligned to Mr Xi himself.

As chairman of the Central Military Commission (CMC) heads the PLA, Mr Xi has presided over the most sweeping reforms to the PLA's power structure since the CCP took power in 1949.

In January 2016, the PLA's four powerful headquarters were abolished and their functions spread into 15 agencies under the CMC, a move widely seen as a decentralisation of power at the top echelons of the military leadership.

Prior to the restructuring, analysts said the heads of the four General Departments wielded such clout that civilian CMC chairs before Mr Xi were often sidelined.

"By dividing them into smaller organs and making them report directly to Xi himself, it's a way for him to exert direct control over the PLA," said S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies' China expert Hoo Tiang Boon.

"It shows that he's a very hands-on type of leader, especially in military matters."

Mr Xi's control of the military would grow: a month later, China's seven regional military areas were regrouped into five theatre commands, and their leadership reshuffled.

In April, Mr Xi was made commander-in-chief of a new joint command headquarters, a sign that he would be more involved in getting each arm of the restructured PLA to operate together better.

In tandem with military reforms was increased scrutiny of the top brass under Mr Xi's anti-corruption campaign.

Since 2012, more than 40 generals have been arrested for offences like bribery, including two CMC vice-chairmen Xu Caihou and Guo Boxiong, who had served under Mr Xi's predecessor Hu Jintao.

While critics said Mr Xi wielded his anti-graft campaign as a way of bringing the PLA high command in line, the reforms have also significantly altered the size and shape of the world's largest standing army.

In 2013, Mr Xi announced that the 2.3 million-strong PLA would cut 300,000 troops.

Further cuts to the army were announced in July this year, while the navy's numbers would be boosted, in line with a 2015 defence white paper which stated that "the traditional mentality that land outweighs sea must be abandoned".

As part of this rebalancing of the PLA's service arms, Mr Xi oversaw in 2015 the elevation of the PLA's rocket force to a full service, while a new Strategic Support Force responsible for space, cyber and electronic warfare was also formed.

Reforms of the next few years will likely focus on institutionalising these changes down to the rank and file, even as China moves to project military power further afield as its overseas interests grow, said Dr Hoo.

"The broad, structural changes have been made, so now it's a matter of slowly going down the levels and getting key personnel in there to implement these changes," he said.

Even as further changes to China's armed forces are certain, Mr Xi has confidently declared that China has taken the "historic step of building a military force with Chinese characteristics".

In a speech on Aug 1 commemorating the 90th anniversary of the founding of the PLA , he said: "The people's army now has a new system, a new structure, a new pattern and a new look."

Can China root out extreme poverty by 2021?

Eliminating extreme poverty in China is part of Mr Xi's central agenda to build a "xiaokang", or moderately prosperous society by 2020, and he is likely to speak about it when he delivers his work report during the 19th Party Congress.

Ensuring that there are no abject poor in China by the time China celebrates the 100th anniversary of the founding of the Chinese Communist Party in 2021, is "the baseline task" of this project, Mr Xi has said.

China has already achieved the feat of reducing the number of people living in poverty by over 700 million since 1980, or three-quarters of global poverty reduction in this period.

But more than 70 million people were still under the poverty line of 2,300 yuan (S$472) a year in 2015, prompting Mr Xi to kick into overdrive his poverty-reduction campaign that year.

Analysts said the drive to erase poverty, besides being closely tied to China's centenary goal, goes to the heart of the CCP's legitimacy and authority to rule.

The CCP came to power in 1949 with the firm support of the rural poor, and it was in the countryside that its earliest revolutionary bases were started.

Decades of reform and opening up have made segments of Chinese society rich, but also raised income inequality to among the world's worst, a recipe for social instability.

The government has focused most of its efforts on raising the living standards of those in remote villages, many of whom are subsistence farmers.

Government programmes to improve their lot range from industrial development and job creation, to social security payments and relocation assistance for those staying in areas with few natural resources.

But local governments have also been tasked to help these villages find alternate income sources, such as by developing agri-tourism and homestays, cultivating specialty products that each region is known for, and tapping e-commerce to raise awareness and sales volumes.

Small landholding farmers have also been encouraged to join cooperatives that better realise economies of scale, and in exchange for guaranteed yearly payments.

Such efforts have started to bear fruits, Minister for Agriculture Han Changfu said in September, noting that rural-urban income gap has begun to shrink since 2012.

Rural incomes have also grown faster than that of urban residents' in recent years, with the income of farmers in poverty-stricken areas growing the fastest, at over 10 per cent a year, he added.

But Mr Xi has recognised that the law of diminishing returns means the last 40 million people still under the poverty line will be the most difficult to lift up, with many either old, sick or disabled.

This is why there are persistent rumours in recent months that he is pushing hard for his political thought to be written into the CCP's charter during the congress. Analysts said such a move will put the leader's personal stamp on the objective of achieving a moderately prosperous society by 2020, which has seen resistance from vested interests.

"Revision of the party Constitution to reflect the Xi leadership's goals and policies, abetted by the now permanent campaign to study Xi's speeches and the party Constitution, may revitalise the flagging impetus behind the 2020 project," wrote Stanford University China expert, Dr Alice Miller, in September.

Can the world's second largest economy continue to grow?

The Chinese economy has not been in the spotlight in the past five years as Mr Xi has focused on fighting corruption, reforming the military and consolidating power.

Growth has been slowing steadily since 2012. Last year, it dipped to 6.7 per cent, the slowest expansion seen by the world's No 2 economy in 26 years.

According to Mr Xi, the economy has entered a "new normal", characterised by slower but steadier growth, which is driven mainly by consumption rather than investments and exports.

In the first half of this year, consumption accounted for 63.4 per cent of gross domestic product (GDP) growth, up from 51.8 per cent in 2012.

The structure of the economy has also shifted away from manufacturing. The services sector's share of the GDP rose to 51.6 per cent in 2016, after crossing the 50 per cent mark for the first time in 2015.

In search of new growth drivers, Mr Xi had, in 2013, unveiled an ambitious plan to revive two ancient trading routes on land and via sea.

These link China to other parts of Asia, the Middle East, Africa and Europe through a series of roads, railways, ports and industrial parks.

Known as the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), it is a way for China to export its overcapacity, build internationally-competitive Chinese companies and stimulate growth in its western provinces.

Analysts say Mr Xi has done a fairly good job in balancing the conflicting demands of maintaining social stability, growing the economy and pushing for reforms during his first term.

One good indicator is the number of jobs created in the past five years. Despite a slowing economy, 13 million new jobs were created each year from 2013 to 2016, surpassing the official target by 30 per cent.

The government under Mr Xi has taken steps to reduce the overcapacity in steel and coal production, rein in runaway housing prices in major cities, and tackle the ballooning debt problem.

But he has found it hard to push these economic policies due to resistance on the ground.

This is not without reason as local governments get only about half of the fiscal revenue, while having to pay for more than 80 per cent of the spending.

With the success of the anti-corruption campaign that has helped weed out uncooperative officials and placed authority firmly in Mr Xi's hands, it can be expected that he will focus more on the economy in his second five-year term.

This could mean settling for even slower growth in order to push bolder moves to contain housing bubbles and reduce high debt levels, which are concentrated in state-owned enterprises.

Many observers have warned that China's credit binge, if left unchecked, could trigger a financial crisis and derail the economy completely.

Analysts say that given the current pace of economic expansion, Mr Xi has room to let growth slide to 6.3 per cent for the next three years and still achieve his target of doubling 2010 GDP and per capita income by 2020.

Externally, Mr Xi will ramp up his signature BRI, which has gained some momentum this year after the inaugural BRI forum.

This could also pave the way for more liberalisation measures for the Chinese currency, putting the yuan back on track along the internationalisation path.

Some analysts have, however, said that it is impossible for Mr Xi to keep the economy going under state domination and eradicate corruption at the same time.

This is because his sweeping anti-corruption campaign has stalled economic growth by dampening the demand for luxury goods, noted Assistant Professor Ang Yuen Yuen of the University of Michigan.

"The larger problem is that the campaign has forced local officials to become highly risk averse and unwilling to attempt policy innovations on the ground," she wrote in an article on the website The Conversation. "But China's speedy growth in the past decades was precisely fuelled by the bold initiatives and discretionary actions of local leaders."

Local governments have been the primary agents of improvisation and adaptation to changing conditions.

How will an assertive China flex its muscles?

There is little doubt that Mr Xi has been more assertive than his predecessors in the international arena since coming to power in 2012.

But China's growing assertiveness was already evident after the 2008 Beijing Olympics, regarded as the Asian economic powerhouse's coming-out party, and especially after the 2008-2009 financial crisis, which saw China's surging confidence against growing self-doubt in the West.

It was in 2009 that China revealed a nine-dash line map that lays claim to almost all of the South China Sea, in response to the continental shelf claims submitted jointly by Malaysia and Vietnam to the United Nations. The Scarborough Shoal standoff between China and the Philippines and China's subsequent blocking of access to the area to Philippine fishermen took place under then President Hu Jintao's watch in 2012.

However, Mr Xi's own personality and a new set of circumstances somewhat favourable to China have allowed and impelled him to go further than his predecessors have internationally.

"Xi has ... demonstrated that he is a decisive leader, stronger than his predecessor and determined not only to manage China but also to transform it to meet huge unsolved challenges, primarily at home but also abroad," wrote Mr Jeffrey Bader of the Brookings Institution.

The China under Mr Xi also has new capabilities and new needs and interests.

It is the world's second-largest economy and largest trading country. It is also the world's largest manufacturing country and sits in the middle of a regional manufacturing hub.

Its military after two decades of double-digit growth in its budget has developed stronger capabilities, commissioning its first aircraft carrier in 2012, among other things.

China, from its opening up and reforms beginning in 1978, has been a beneficiary of the international order, becoming more integrated with it as its economy became more intertwined with those of the rest of the world.

While China under Mr Xi participates fully in major institutions of the international order like the World Bank, it has also sought to influence that order, for example, by starting the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank.

Still, wrote Professor Francois Godement of the European Council on Foreign Relations, China has "deep and unacknowledged interests in maintaining a stable order because of its integration in the global economy".

"A disruption to that order would − by necessity − be a disruption to its own economic interests," he wrote.

Mr Xi now faces both opportunities and challenges brought about by a more isolationist United States under President Donald Trump and a Western world grappling with a populist backlash against globalisation.

He has shown China's readiness to step into the space left by the US. He told the World Economic Forum in January this year that the world "must remain committed to developing global free trade and investment, promote trade and investment liberalisation and facilitation through opening up and say no to protectionism".

He added: "We should adhere to multilateralism to uphold the authority and efficacy of multilateral institutions."

At September's Brics summit that gathered leaders of the world's major emerging economies - Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa - Mr Xi sought to galvanise the grouping to play a more influential role in shaping the international order.

"We need to speak with one voice and jointly present our solutions to issues concerning international peace and development," he said adding: "This ... will help safeguard our common interests."

He stressed the need to reform the global economic governance, "increase representation and voice of the emerging market and developing countries" and to inject new impetus into efforts to address the development gap between the north and south, and boost global growth.

Under Mr Xi, this policy direction of participation in and also shaping of the international order to something more to Beijing's liking is likely to continue after the 19th party congress.